The Magic Music Box| The Memory-Maker

Project Details

Awards & Nominations

The Magic Music Box has received the following awards and nominations. Way to go!

The Challenge | The Memory-Maker

Magic Music Box

Using a music box to store infomation on Venus and transmitting it.

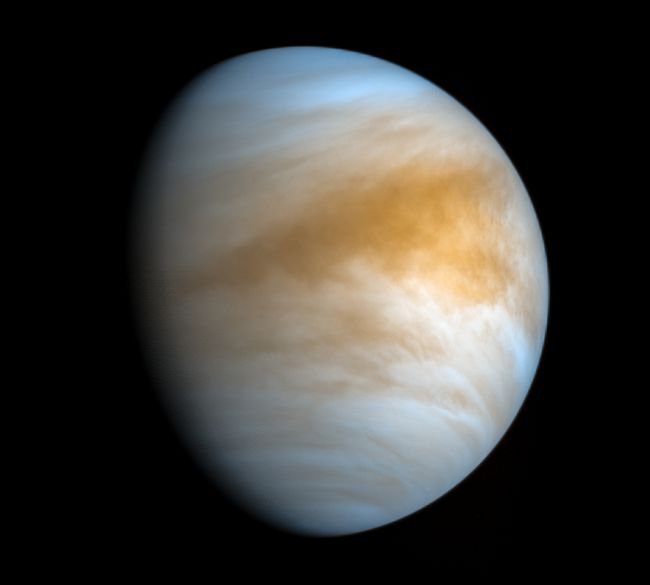

The Memory Maker was immediately the project that caught our interest, due to the sheer difficulties that face anything attempting to survive Venus's harsh, toxic landscape. Practicality is not necessarily the answer in such a scenario and can, in fact, prove to be a hindrance. Unlike other challenges that have a viable answer ready to be coded and deployed, this project is far more abstract and features more of an element of creative, outside-the-box thinking over the straight-forward.

Often, when coming up with solutions to particularly vexing problems, people look to the future. They look to what has yet to be invented, to what is cutting-edge in the here-and-now. They forget that in ten years this "cutting-edge technology" will be just as relevant as what was the pinnacle of innovation in the 1990's. As such, we decided that to combat the problem of storing data on Venus with limited use of electronics, it was time to change direction and look backwards at what has already been accomplished.

The Magic Music Box is very simple, and yet might just be the answer. Taking inspiration from the Atanasoff-Berry Computers and modern-day music boxes, we determined that the best way to store the data was to imprint the data in binary form on a thin strip of shape memory alloy (likely Ni-Ti-Pa due to its capability to work at much higher temperatures than the majority of metal alloys). Small dents are embedded into the metal and a reflective mirror passes along it, shifting in angle over the dents. When the mirror's angle of incidence changes from the slight change in height, the EM waves from an orbiting satellite is reflected back at it, and registers as a positive "one" signal - and where there is no dent, the angle remains enough to reflect the signal back into space, registering as a negative "zero" signal. The metal can be rewritten many times by passing a small electric charge through it, allowing more data to be written and transmitted.

Using NASA's research on Venus, we know that the current longest-surviving mission to Venus lasted a little over two hours. The cost is difficult to estimate, as the Venera launches were during the USSR's reign and information was closely guarded, but the amount of data revealed in just 127 minutes was extraordinary for the advancement of our understanding of Venus and is still used today. 43 missions to Venus, and 35% failed before even reaching Venus. 37% if we include partial failures. Of those 43, 7 missions were landers and 5 of these were successful or mostly successful. This confirms that, while difficult, it is possible to land a mission on Venus. Our idea is, at its current stage, meant to be integrated with a mission and should be attached as part of the craft as the magic music box is meant for storage and basic transmission of data, not the collection.

Clearly this system is a basic one, utilising ideas from the early 1940s. There are a few drawbacks. The metal can only be rewritten so many times before wear and tear degrades it, as is the case for most things not maintained. However, as a workable solution, it is viable and, more importantly, possible. It is not prone to the burning end that most electronics sent to Venus face. The simplicity of the system means it ought to be low in cost and high in informational revenue. The record for a mission to Venus that successfully sent back data was 127 minutes, but it is entirely likely that this possible solution can allow for even longer periods of time on our solar system's harshest world.