Beun Team Twente| Build a Planet

Project Details

Awards & Nominations

Beun Team Twente has received the following awards and nominations. Way to go!

The Challenge | Build a Planet

The planet factory

The planet factory is a game where the player tries to design a habitable planet as his/her new home and keep it habitable for as long as possible. The player learns about how different features influence the habitability of planets.

THE PLANET FACTORY

The Team

Beun Team Twente is a team of 4 electrical engineering students and a chemistry student. We worked together in other challenges, like the famous Scrapheap challenge on our university. We participate in the challenge since we have a passion for space, engineering and entrepreneurship.

The story

The earth gets crowded and the fuller it gets, the more uncomfortable you get. You need more SPACE! Then, you see a commercial on TV: the planet factory. It allows you to design your own planet and they offer to build it for you. This is exactly what you needed! However, you should design your planet carefully ...because you want to spend your life there!

The Goal of the Game

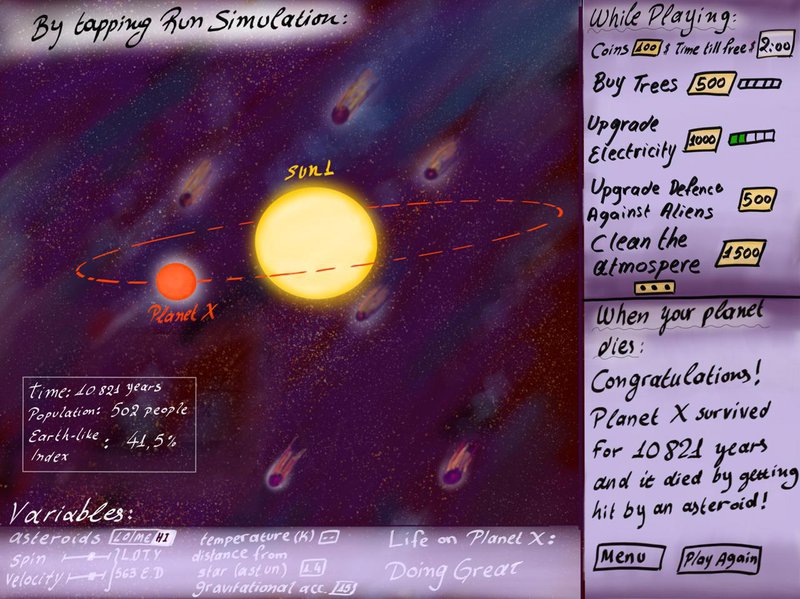

The player’s first goal is to design a vital planet. There are many characteristics of it that they can change, such as its mass, temperature, diameter and many more. After the player creates a planet that is habitable, they can begin the game by clicking 'run simulation’. Time begins. The player now aims to maintain life on the planet for as long as possible by upgrading features of it. At the same time, external forces, such as asteroids, will try to vanquish life on it.

The Gaming Element

An original game in which you are needed to design a habitable planet for humans to migrate! As you build your planet you must take care of all of the essentials, like the temperature, the trajectory and the gravitational acceleration. With this app you can experiment with all the different variables, get engaged with science and have fun doing so. Learn about how changing features of the planet can affect life on it and try to make it last in time by upgrading it. You will need a good start, so be sure your planet has the best foundations. Earn coins for your upgrades and add trees, help your people who suffered a natural disaster and avoid the toxic-atmosphere zombie apocalypse! Keep your people safe, your planet’s core stable and the aliens away.

To keep the game engaging, the star which the planet will orbit could be randomized. Such a parameter would influence the habitability, such that the gameplay is never the same and therefore the user has to adapt his design to these external influences. The eventual gameplay could be similar to games like SimCity, where the player tries to manage a city. Ideally, it could be an extension of such well known games. With a possible implementation of highscores, the player will then aim to improve their score and share it with their friends.

The Educational Value

The player’s goal is to test the different parameters and their interactions with one another, in order to create an environment suitable for life. Understand which features make a planet more stable and therefore more probable to last in time. Although fun elements make the game more enjoyable, this is an important educational experience for everyone interested in learning a thing or two about planets. What a better way to learn the significance of a star’s temperature and its distance from our planet than with a simulation game? High-schoolers can get an idea of what a star really is and older adults can get inspired and get involved in science. Since overpopulation is a real earth issue, reaching out to other habitable planets might be a more real than just a game in the future.

Players work in a fun environment with real NASA data and learn about the influences on the habitability.

The Data

The data that we used is from the Planetary Habitability Laboratory (PHL), from the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo. We used the PHL's Exoplanets Catalog [1], which came from the Nasa Exoplanet Archive [2]. For the proof of concept, 7 features were selected from this database, which are explained in the section below. The target outputs of the models are the habitable index and earth-similarity index in the dataset.

What we Did

Habitable or not?

The work we did during the hackathon focused primarily in designing the planet and indicate whether it is vital or not and how earth-like it is. The concept of time, is an idea for future implementation. As mentioned, we used the PHL Exoplanet Catalog. We extracted 7 features for a total of 4048 exoplanets, which are listed below:

- P_MASS: the mass of the planet (with respect to the mass of earth)

- P_RADIUS: the radius of the planet (with respect to the radius of earth)

- P_GRAVITY: planet gravity (with respect to the earth units)

- P_DISTANCE: planet mean distance from the star. (in astronomical units). The star name is also part of the big database. We use a universal star for the design planet and use the distance as a measure to A star.

- P_FLUX: the planet mean stellar flux (with respect to the earth units)

- P_TEMP_EQUIL: the planet equilibrium temperature (in Kelvin)

- P_TYPE_TEMP: Planet thermal type (PHL thermal classification), which can be either hot, warm, cold or unknown.

Being aware of the time limitations in the hackathon, only specific features were chosen, the ones can give the audience the basic idea of what a planet requires to become more suitable for life. They are fundamental features used to identify whether a planet can host life, but more advanced features can be easily added to the model to make it more convoluted and accurate.

Using machine learning, we designed a classification method for the habitability of the planet. The 4048 data-samples were used with the aforementioned features (actually, only a part was used, see 'challenges'). We used P_HABITABLE from the dataset as labels. This feature has a value 0 for non-inhabitable, 1 for maybe habitable and 2 for habitable. We used a support vector machine and we trained for all features a different classifier. We did this to monitor the individual relations between the feature and the habitability, which can also provide feedback to the user on how to improve the score of the planet. The output per classifier is a score for each class, that sum to 1. We also scored the features in their relation with the habitability, using chi2. We normalized the scores, to create weights for the features.

Finally, the results from all features are fused to give a final prediction. This score is the weighted-average of the output per classifier, which uses corresponding weight of the feature. It is a value between 0 and 2, where 0 means uninhabitable and 2 means habitable. The idea is to transform this into a percentage.

We also mentioned the earth-similiarity index, which is a percentage score. Since it is a continuous value, we used a regression based neural networks with layout (20,10,1). The prediction is a value between 0 and 1, where 0 means not similar to earth at all and 1 means completely similar. We computed again the weights of the features, but instead using chi2, we used mutual-info regression score.

The final score is the sum of the outputs per classifier multiplied with the corresponding weight of the feature.

The machine-learning models were coded in Python. For the first classifier, we used the sklearn SVC class, and for the neural network we used the sklearn MLPregression. For scoring the features, we used sklearn SelectKbest on the training data.

CHALLENGES

Weights: The features are not equally important for the classification. We solved this by scoring the features and used the normalized scores as weights.

Classification of habitability: The dataset of 4048 samples was unbalanced in the sense that there were many more samples non habitable (value = 0) than probably habitable (value = 1) and habitable (value =2). The predicted output of the classifier became always 0. To prevent this, we used less datasamples that belong to the non habitable class.

Missing Values: The dataset had many missing values even for the basic features. In order to solve these exceptions, they are filled using the mean value of the feature column. This wouldn’t influence the variance or the mean of the data and therefore the classifiers aren’t influenced.

Visualization

The proof of concept program uses the Processing Java framework to visualize the created planet orbiting its star. This software is easy to use and is ideal for prototyping animations of this type. However, for the actual product, a comprehensive game engine should be used or developed. This would allow for better graphical performance, improved scalability and—in the case of portable devices—increased battery life.

In a released product, all the features of the planet will be visualized during the design phase and when the simulation is running. However, the prototype game only visualizes the following features:

- Temperature (Type)

The color of the planet changes depending on its temperature: for low temperatures (below 273.15K), it will turn ice blue. Then, as the temperature increases, it turns gray. If the temperature rises above 800K it starts to glow orange and then white hot. - Size of Planet

The planet is dynamically changing during the design phase based on the user’s input. - Distance to the Star

The distance to the planet’s star is also dynamically visualized as the user changes the sliders.

The graphical user interface in Processing was done using the ControlP5 library is used. This library provides buttons and sliders and event handlers. This has greatly sped up the development process.

Connection / user input

In the proof of concept, the user is able to change the value of each parameter using a slider. At this time, any dependencies between the parameters were neglected. This means that, for example, if the mass of the planet is increased, the value of the planet’s gravity is unchanged. In a possible future product these dependencies should be evaluated and included in order to make the gameplay as realistic as possible.

The program in its current state collects the data from the sliders and runs the python program that contains the trained data. The python program then returns whether the planet has any chances of supporting life. The program also returns a value that shows how ‘earth-like’ the planet is. Finally, when the planet is habitable, the button to go to the next stage appears. For now, this button does nothing but closing the program. In the possible future this button will allow you to play the actual game.

Next Steps

Engaging gameplay:

The current game should be improved in terms of content. By having the player make progress through the development of his/her planets in terms of available tools and items (AKA rewards). Additionally, the difficulty should increase to keep challenging the player. The result would be gameplay that encourages the player to keep playing the game, and thus learning more about the features of a planet.

Randomize star:

In the dataset that we used, there is also a lot of information on the star that the exoplanets belong to. This means, we could also find out the relation between features related to the star and the habitability of the planet. To make the game more challenging and add external influences, we could randomize the star at every new design of a planet and include the results in the calculation of habitability.

Time:

After the planets habitability is computed, the player can start. We want to include time as a factor as the player needs to keep its planet livable for as long as possible. There are also external influences that can happen in time, such as incoming asteroids, earthquakes or other unforeseen phenomena.

Dependencies:

As mentioned before, the gameplay can become more realistic by making the parameters dependent on each other. This will mean that the planet generated could exist, adding to the educational value.

Open-source Code

All the code is hosted on Github and is free to use and modify: https://github.com/ant0nisk/ThePlanetFactory

References

[1] PHL's Exoplanets Catalog. Online (Accessed 19-Oct-2019): phl.upr.edu/projects/habitable-exoplanets-catalog/data/database

[2] Nasa Expolanet Archive. Online (Accessed 19-Oct-2019): exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu